The Fight for Environmental Justice in Federally Assisted Housing

June 2020

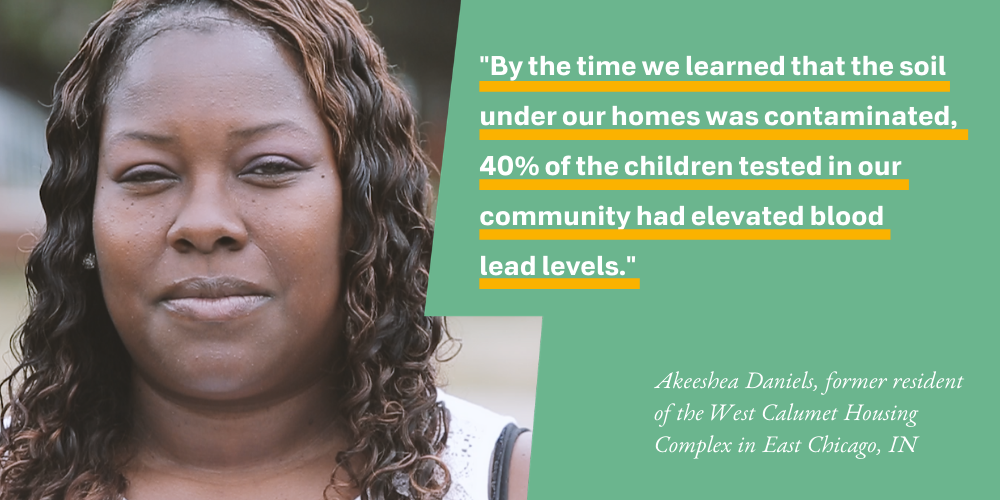

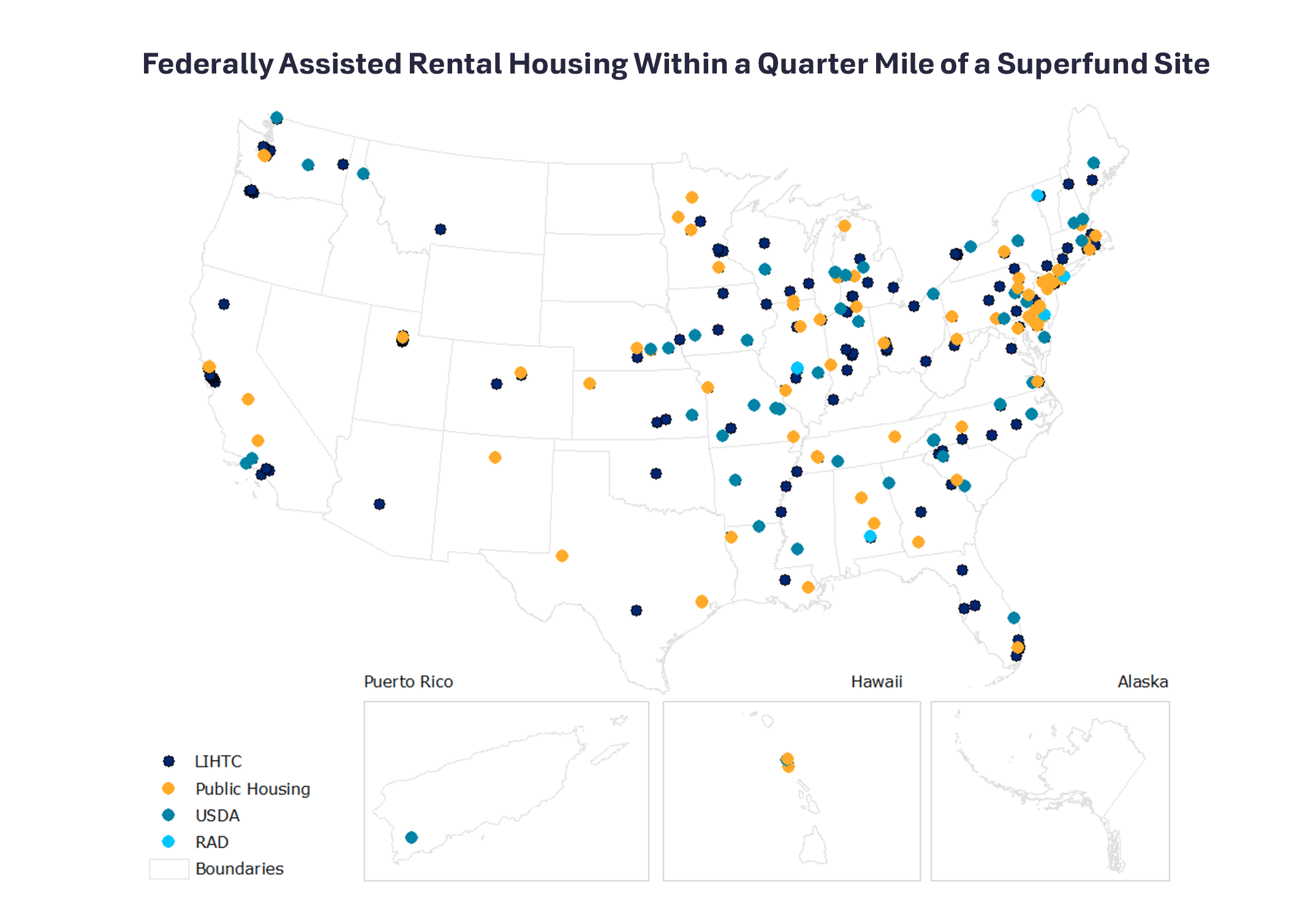

Across the country, tens of thousands of families living in federally assisted housing are living on dangerously contaminated land where they face an urgent and ongoing environmental and health crisis.

The federal government has invested billions of dollars in the construction and preservation of affordable housing but has done little to protect affordable housing residents from toxic and hazardous environments. As a result, exposed residents are suffering substantial, irreversible, and life-altering health conditions, ranging from neurological and biological damage to cancer.

This report examines the historical context surrounding the siting and redevelopment of federally assisted housing and environmental issues encountered by residents of contaminated sites, tells stories of community activism in the face of that reality, and makes recommendations for reducing toxic exposures and arming residents with the power to dictate what happens to their families and communities.

Read the full report, watch a webinar on the report’s findings and recommendations, or explore more below.

First, it is critical that the directly impacted community be centered at all stages of decision making, as it is ultimately their health, future, and community that is at risk. Absent meaningful engagement, and the ability of directly impacted communities to drive decision-making, environmental justice cannot be realized.

Second, primary prevention — preventing environmental contamination and associated health consequences — is the central goal. Primary prevention means that efforts are taken to prevent physical harm and disease, rather than treating poor health conditions after they materialize. It is the most just, reliable, and cost-effective measure to protect children and individuals from exposure to hazards.

Third, there must be a real financial commitment to addressing these issues. Many of the failures across health, housing, and environmental programs stem from an insufficient commitment of financial resources. Polluters should bear the cost of full implementation of a remediation that is protective of human health and the environment and reflects the impacted community’s priorities. Environmental, health, and housing agencies should also receive federal appropriations at levels consistent with what is needed to investigate contamination and to protect impacted communities, as determined in large part by those communities.

Finally, in order to achieve environmental justice, a federal cross-disciplinary approach focused on primary prevention and addressing the needs of impacted communities is critical. Currently, federal agencies operate in silos and fail to listen to impacted communities, communicate with one another, or prioritize the principles of environmental justice in their actions. Thus, effective interagency practices should be developed and implemented.

Federal agencies should promulgate regulations to improve and expand on interagency accountability to impacted communities nationwide. Interagency regulations could outline the expectations and responsibilities of all agencies involved in the cleanup process and facilitate the flow of vital information to impacted communities.

There should be regular, early resident engagement, especially in any discussions or visioning processes for redevelopment of Superfund sites, that should pay particular attention to avoiding gentrification that displaces environmental justice communities. Special consideration should be paid to preserving and creating low-income housing and employment opportunities in the community.

Cross-agency collaboration is critical to ensuring communities are able to achieve environmental justice. Government agencies should enter into site-specific memoranda of agreement governing notice, community engagement, and cleanup. Agencies should likewise promulgate regulations to improve and expand on interagency accountability to environmentally impacted communities nationwide. At the same time, housing, health, and environmental laws and policies, and the public agencies that implement and enforce those laws and policies, must collectively and cooperatively respond to this crisis.

When a new site is listed on the National Priorities List, residents should receive actual notice of the listing and any associated health risks. In particular, federal agencies must ensure that tenants of and applicants for federally assisted housing receive notice of environmental hazards and health risks. Notices should explain the contamination, its impact on human health, and why individuals should be tested.

Federal housing agencies must ensure robust public participation when any housing project or proposal presents human health risks due to proximity to an unremediated Superfund site. Likewise, when state and local funds are used for housing development or rehabilitation, state and local government should ensure there is robust public participation when any federal housing project is proposed that may present an environmental justice concern.

HUD must update its guidance to ensure that EPA is notified before a NEPA environmental review is prepared at federally assisted housing within one mile of a Superfund site. HUD should likewise sync its online tools and most current guidance to ensure high-quality reviews under NEPA. Further, all new construction, redevelopment, and rehabilitation of federally assisted housing should trigger appropriate civil rights review, and the nation’s largest creator of new federally assisted housing, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program, should be subject to NEPA.

Federal housing agencies and local public housing authorities must improve their environmental assessment process, including engaging environmental experts to handle issues related to complex hazardous waste sites. The lack of environmental expertise within HUD or local housing authorities can lead to dangerously deficient plans that do not appropriately account for actual risks and, in some cases, can actually create new risks.

EPA should provide information concerning contamination to the public at the same time that it provides information to potentially responsible parties or when it receives information from them. Members of the public cannot take actions to protect themselves or to advocate for their interests if they do not know or understand the levels or extent of the contamination in their homes and neighborhoods.

Community-based organizations in impacted communities must foster collaboration to tackle contaminated sites near low-income housing, and advocates must work across disciplines to support affected communities. Directly impacted communities can be supported with critical technical assistance in order to navigate the complex funding and legal framework they must understand to achieve their goals and protect the health of their community.

Sites in or near residential areas should be cleaned up to residential cleanup standards. States and EPA should limit or eliminate the use of site-specific relaxed standards that are near residential areas.

EPA’s use of “institutional controls” should not result in recontamination at Superfund sites. Institutional controls are the use of deed restrictions or other legal instruments as part of a cleanup plan to constrain future uses of a contaminated site, on the theory that such restraints will prevent people from being exposed to contamination left in place and, therefore, less contamination needs be remediated. This practice must be scrutinized and disfavored.

Affected communities should have increased access to public benefits, including TANF, SNAP, WIC, and Medicaid. WIC participants should also have supplemental benefits and screenings to mitigate and prevent the effects of environmental exposure. States should be encouraged to use flexibility within Medicaid programs and demonstration projects and the Children’s Health Insurance Program to monitor exposed individuals, especially children with elevated blood lead levels, to provide care coordination, and to identify and remediate environmental hazards.

All federal agencies, including EPA, USDA, and HUD, should update their definitions of lead poisoning to match the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reference value. Because low-level lead poisoning does not have any outward presenting symptoms, early identification of elevated blood lead levels and the source of exposure is critical to protecting children exposed to lead from further neurological damage.

Health interventions should be triggered automatically for all federally assisted households living at or near contaminated sites. Federal housing providers and EPA should work with local and state health departments to ensure adequate notice to tenants. Notices to tenants should clearly explain the contamination, its impact on human health, and why individuals should be tested. Public health departments must make access to testing free and accessible and should offer free onsite testing and prompt follow up.